Like anyone who grew up in Corner Brook, I was always familiar with the name, Captain James Cook. I’d visited “Cook’s Lookout” on Crow Hill, as we always called the national historic site, many times and marveled at the beautiful panoramic view of the Bay of Islands. I’d swim in the frigid but perfectly clear water of Cooks Brook on what passed for a hot summer’s day in Newfoundland until I couldn’t feel my fingers or toes. I knew that he had been the first person to map the Bay of Islands and whenever I’d go up to the lookout, I couldn’t help but wonder what it must have been like sailing up the bay in 1767. Although his wasn’t the first voyage to Western Newfoundland, as a child I would hear that he “discovered” the Bay of Islands; the fact that Newfoundland was already inhabited by Indigenous peoples, like the Beothuk and the Miꞌkmaq, rarely being mentioned.

I recently traveled to two other places, a world away, which I learned were also closely linked to Captain Cook: Australia and Hawaii. As we traveled around New South Wales and Queensland, there seemed to be references to Cook everywhere. A statue of Cook stands in Sydney’s Hyde Park; there are multiple Cooks Lookouts at various scenic points along the coast; and towns, rivers, islands and mountains bear his name. Of course, this is because Cook and his crew landed on Australia’s south east coast in 1770, making them the first Europeans to explore and map that coastline, claiming it for Britain, and the first to make contact with the continent’s Aboriginal people.

Statues of Captain Cook (left) in Corner Brook, Newfoundland and (right) in Sydney, Australia

I struck me as odd that I’d had flown over 17,000 km for nearly 24 hours to see signs pointing to “Cooks Lookout” as if I’d never left Corner Brook. In Australia, Cook has become a controversial and divisive figure, glorified as the country’s founding father by some, and reviled by others as a symbol of the persecution of Indigenous Australians who had inhabited the area long before his arrival. Recently, several statues of Cook have been vandalized by protestors.

Cook’s contemptuous relationship with the native inhabitants of lands he “discovered” is nowhere more apparent than on the islands of Hawaii. No sooner had I flown from Sydney to Honolulu, did I discover that I had arrived in yet another place where Captain Cook’s name would unexpectedly crop up. On a guided tour of the beautiful and historic Moana, the first hotel in Waikiki opened in 1901, our Hawaiian guide told an astounding anecdote about how Cook, the first European to sail to the Hawaiian Islands in 1778, had met a grisly fate at the hands of the Hawaiians just one year later. I hadn’t realized that the man who’s accurate and detailed maps of the Bay of Islands, still being used today, had been murdered by angry natives in Kealakekua Bay, and that the reason for his murder may be even more unbelievable.

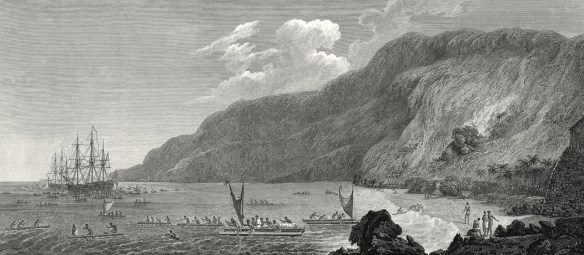

Cook’s ships arriving in Kealakekua Bay, Jan. 17, 1779. John Webber. “A View of Karakakooa.” 1785. The British Museum.

According to our tour guide, Cook was initially mistaken by the Hawaiians for a God, and after realizing they’d been deceived, turned on him in a violent encounter on the beach as Cook and his men attempted to flee. Upon returning home, I did some research to see if the tour guide’s story was true. According to the National Library of Australia, where a collection of rare manuscripts and documents from Cook’s voyages are held, there is evidence to support this version of events. Cook himself wrote about the exuberant reception his ships, the Resolution and the Discovery, received, estimating more than 1000 canoes, as well as thousands more men on surfboards, came out to greet them upon their arrival in Kealakekua Bay on the “Big Island” of Hawaii. Which begs the question of why the Hawaiians were so excited to see these strangers?

Betty Churcher, former Director of the National Gallery of Australia, says “Cook’s arrival at Hawaii coincided with the beginning of an annual religious festival to the God of Peace, Orono [or Lono], when Orono’s banner – which is a large wooden cross some 3 to 4 meters high, draped with tapa cloth – is carried slowly and ceremonially around the island in a clockwise direction, and keeping pace with them also in a clockwise direction were Captain Cook’s tall ships with sails looking for all the world like a banner of Orono tacking backwards and forwards looking for an anchorage. The Hawaiians looking at the sea would have seen what they thought was a huge banner of Orono looming up towards them from the horizon and receding. No wonder they thought that this was a long awaited prophecy of an earthly coming of their god. Captain Cook tells us that he saw the banner of Orono from the deck of the Resolution but he made the same mistake as the Hawaiians; he interpreted what he saw in terms of his culture. He thought the Hawaiians were waving a white flag of peace. Cook finally found a safe anchorage in Kealakekua Bay, by further coincidence, just off shore from the Temple of Orono. Now the Hawaiians were sure. Priests wearing masks accompanied Cook to shore and wherever he went the crowds drew back and prostrated themselves to the ground.”

Modern-day procession signaling the arrival of Makahiki. The wooden staff, with its crosspiece draped in white kapa and feather lei, represents the god Lono. (From Maui Magazine, 2012)

Now, it’s worth noting that not all historians are completely convinced that the Hawaiians believed Cook to be the human incarnation of a God. In any case, Cook enjoyed the hospitality of the Hawaiians, who brought gifts and supplied them with a tremendous amount of food, for about a month. The King of the island himself, Kalani’opu’u, presented Cook with gifts including a ceremonial red and yellow feathered cloak and helmet. What does seem clear though is that the longer he and his crew stayed the less enthusiasm and goodwill the Hawaiians had for the visitors, and they seemed pleased, or possibly relieved, by their departure. If they had initially believed him to be a God, as our tour guide put it, the longer the Hawaiians observed Cook, the more human he must have seemed (for instance, one of Cook’s crewmen died, and Cook himself may have actually been quite ill). The Hawaiians were, no doubt, also concerned about the impact 200 sailors were having on their food supplies.

Cook’s ships left Kealakekua Bay on February 4, 1779, but in a most unfortunate stroke of bad luck ran into a fierce storm, with high winds that snapped the main mast of the Resolution. Cook was forced to return to Kealakekua Bay only a week after he’d departed. This time, their reception was not as celebratory. No one greeted them on the beach. The high chief Kalani’opu’u arrived the next morning to confront Cook, angry, confused and suspicious about why he’d returned. Could this change in attitude have been because the religious festival of Makahiki, during which warfare was forbidden, had ended? Did the Hawaiians feel they had been duped by Cook, who, it was now clearly evident, was no God? Or had the Europeans simply worn out their welcome?

After Cook’s return, the locals began taking items from his ships, and pelting his sailors with rocks when they ventured on shore. Finally, the locals stole one of their cutters (a small boat). On the morning of February 14, an angry Cook went ashore with 10 men, armed with muskets, and a secret, rather badly conceived, plan to abduct Kalani’opu’u and keep him on board until the items were returned. On the beach, surrounded and outnumbered by a mob of hostile Hawaiians fully prepared to defend their ruler, Cook shot and killed a local man. In the chaos that ensued, the crewmen who could swim panicked and fled for the safety of the rowboat waiting just offshore. Four never made it and were killed by the Hawaiians. Captain Cook did not know how to swim.

John Webber, D.P. Dodd. “The Death of Captain Cook at the Sandwich Islands 1779” c. 1785. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

The ship’s surgeon, David Samwell, watching from the deck of the Discovery, described Cook’s final moments. He wrote that a Hawaiian snuck up behind Cook, “and with a large club…gave him a blow on the back of the head, and then precipitately retreated. The stroke seemed to have stunned Captain Cook: he staggered a few paces, then fell on his hand and one knee, and dropped his musket. As he was rising, and before he could recover his feet, another stabbed him in the back of the neck with an iron dagger. He then fell into a bite of water about knee deep, where others crowded upon him, and endeavoured to keep him under.” Finally, he was given another blow with a club, “and he was seen alive no more. They hauled him up lifeless on the rocks.”

In contrast to my experience in Australia, Cook’s name is not as ubiquitous in Hawaii. There are no statues in his honor, except for one difficult to access stone monument in Kealakekua Bay, erected by the British (the plaque tactfully reads that he “fell” near this spot). I wondered whether there was a monument to the 17 Hawaiians also killed on the beach that day. European contact, like in so many other places, would prove to be devastating to the population of native Hawaiians. Today, many Hawaiians take a certain pride in being the people who killed Captain Cook.

After leaving the island of Oahu, I returned to my own little island in the north Atlantic with a new perspective on Captain Cook, the man credited with (literally) putting us on the map. As many times as I’d imagined him sailing up the bay over 250 years ago, I suppose I had never given much thought to where he went and what he did after he left Newfoundland, and Cook is a far more complicated and controversial figure than I had realized.

– Crystal Rose

Hello everyone! Welcome to this blog. I’m Crystal, a Corner Brooker and an academic Librarian. I am currently working on a research project about the local history of Corner Brook – including Curling and Humbermouth – and the surrounding Bay of Islands area.

Hello everyone! Welcome to this blog. I’m Crystal, a Corner Brooker and an academic Librarian. I am currently working on a research project about the local history of Corner Brook – including Curling and Humbermouth – and the surrounding Bay of Islands area.